Portugal, according to a new study published in medical journal The Lancet, has an average birth rate of 1.3 children per woman, which is the second lowest birth rate in Europe and one of the lowest in the world.

This, the research suggests, is largely due to women prioritising professional careers as well as easy access to health care.

Portugal is among a worldwide group of just 91 countries where the average birth rate sits below two children.

Within Europe, only Cyprus has a lower birth rate.

The study by the University of Washington, published in The Lancet and reported by Spanish news agency Efe, shows that in the EU, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus all have birth rates that fall below the European average of 1.6 children.

Spain has an average of 1.4 children per woman, and Cyprus just one child per woman.

On the other hand, the study shows, Niger is the country where women have most children, at an average of seven.

Niger leads the birth list (7.1), followed by Chad (6.7), Somalia (6.1) and Mali (6).

“Low birth rates reflect ease of access to health services and contraceptive methods, but also the fact that many women decide to delay or give up maternity leave to prolong their education and pursue employment opportunities,” said lead study author Professor Christopher Murray.

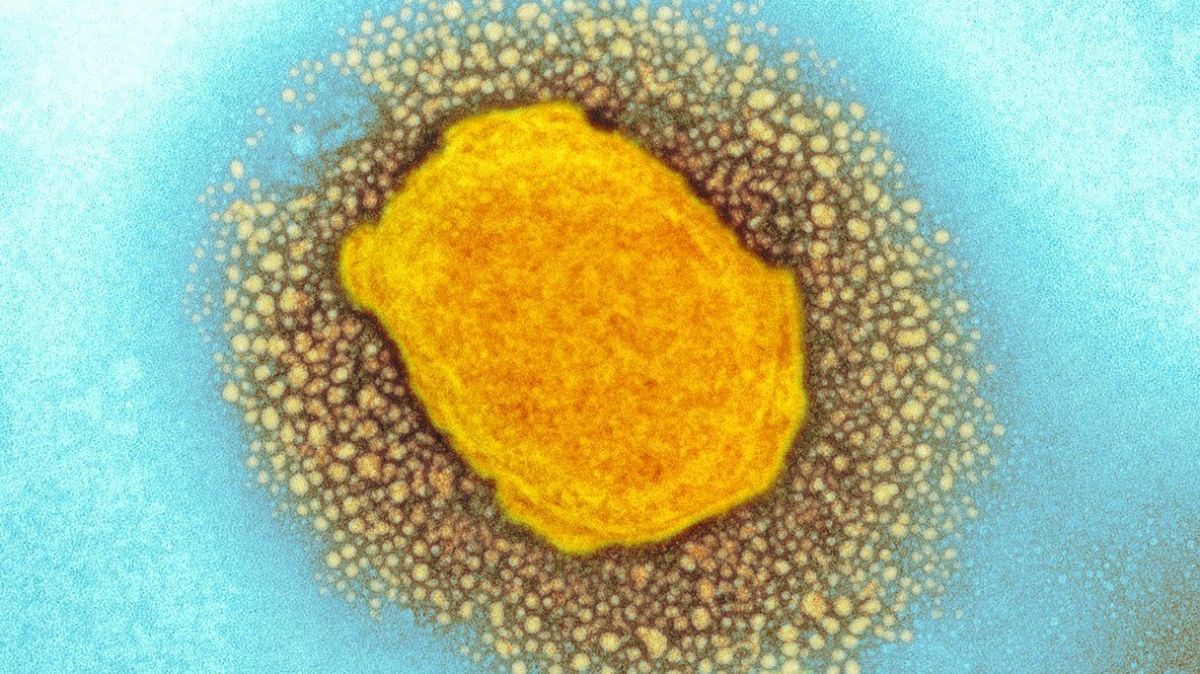

Meanwhile, the same study warned there has been a remarkable global decline in the number of children women are having.

Researchers found fertility rate falls mean nearly half of all countries are now facing a “baby bust” - meaning there are insufficient children to maintain their population size.

The researchers said the findings were a “huge surprise” and there would be profound consequences for societies with “more grandparents than grandchildren”.

Speaking to the BBC, Professor Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, said: “We’ve reached this watershed where half of countries have fertility rates below the replacement level, so if nothing happens the populations will decline in those countries.

“It’s a remarkable transition. It’s a surprise even to people like myself; the idea that it’s half the countries in the world will be a huge surprise to people”.

Generally, the more economically developed countries including most of Europe, the US, South Korea and Australia have lower fertility rates. This is, however, to some extent offset by migration and death rates, and does not, as yet, mean the populations in these countries are falling.

Meanwhile local councillors from parts of Portugal and Spain have also warned of population decline, particularly in rural inland areas, due to poor infrastructures and accessibility.

About 30 councillors from the Alto Alentejo and Beira Baixa regions in Portugal and the province of Cáceres, in Spain, are due to meet to warn the governments of both countries about the problems of rural population decline, officials said last Friday.

The warning that the councillors intend to sound through this initiative, was given on Sunday in Montalvão, in the municipality of Nisa, in Portugal’s inland Portalegre district, during a meeting that also discussed the lack of accessibility, which affects the connections of these areas separated by the Tagus and Sever rivers.

“Population decline is a problem and this meeting serves to raise awareness of our needs, and one of the ways to avoid isolation is through links that can bring together these three regions”, said the president of the Parish Council of Montalvão, José Possidónio, in comments to Lusa News Agency.

The construction of a link or the daily opening of the bridge connecting Montalvão to the Spanish village of Cedillo (Cáceres) is one of the local authorities’ main demands.

While the governments of Spain and Portugal are not yet implementing any project, populations on both sides of the border “only meet”” at weekends, when the Spanish hydroelectric company Iberdrola removes the padlocks from the gates and reopens the bridge in the confluence of the Tejo and Sever rivers to traffic.

The two communities are 15 kilometres from each other, but during the week, the populations have to travel about 120 kilometres to be able to meet or trade.

A number of Portuguese municipalities have in recent years launched initiatives to attract young families to them, which include tax breaks and incentives for those looking to start families.

Portugal has been battling to boost its struggling birth rate and ageing population for almost a decade, having registered negative results since 2009.

Exacerbating this, according to newspaper Jornal de Notícias, is news that Portugal last year lost some 32,000 residents.

However, last autumn it did experience something of a ‘baby boom’, for the first time in almost a decade, with over 1,000 babies born in October and November 2017.

Portugal reflects global decline in fertility rates with one of lowest birth rates in world

in News · 15 Nov 2018, 10:11 · 1 Comments

Thank you Kanye very cool!

By Trump Donald J from Other on 02 Oct 2019, 23:53