Ukraine’s top commander, General Oleksandr Syrskyi, retorted that Ukraine now controls one thousand square km. of Russian territory. That may be true, but it doesn’t count for much because Ukraine’s total territory is more than 17 million square km.

Besides, Ukraine’s foreign ministry spokesperson Heorhii Tykhyi said on Tuesday that “Ukraine is not interested in taking the territory of the Kursk region.” Sooner or later, that territory will go back to Russian control.

It would be very hard for Kyiv to hold Kursk indefinitely. The Ukrainians are desperate for military manpower and the real rewards of the Kursk operation – undermining Russian President Vladimir Putin’s narrative and showing Western supporters that Ukraine is still in the game – have already been collected. Now go home before something bad happens.

Another reason not to keep Kursk region is political. Putin plans to conquer and keep as much of Ukraine as he can, so Russians are taught to see Ukrainians as deluded people whose destiny is to be part of ‘Greater Russia’. Most Ukrainians have no imperial delusions and see Russians simply as enemies, so why would they want to rule over them permanently?

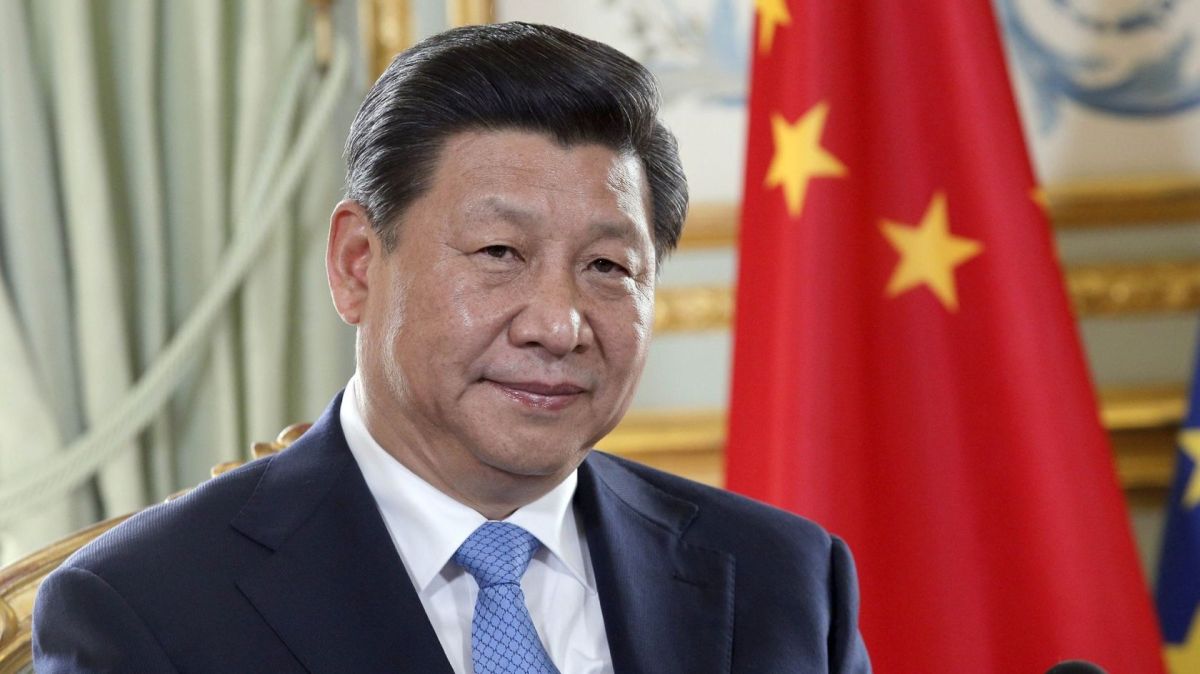

Yet there is also a consideration that might prompt Ukraine to hang onto captured Russian territory for as long as possible. Putin himself put his finger on it when he said on Monday that Ukrainians, “with the help of their Western masters, are trying to improve their future negotiating positions.”

Never mind the reflexive propaganda guff about ‘Western masters’. Putin is accusing Ukraine of planning to take part of Kursk region and its Russian population hostage, holding them to swap for Ukrainian territories held hostage by the Russians when ceasefire talks finally get underway.

Putin always says he is ready for a ceasefire, although only on his own extreme terms: Russia gets all of four large Ukrainian regions, none of which are entirely controlled by Russian troops yet.

Now he reveals that in his opinion the Ukrainians (or rather, in his own mind, their ‘Western masters’) are also contemplating a ceasefire. As indeed they should, for reasons both short-term and long-term.

The short-term reason is Donald Trump, who would instantly sell them down the river if he wins the presidency in November. In that case, Ukraine’s European NATO allies would go on supplying them with arms and money, but Kyiv would no longer have any hope of victory and it would need to make a deal that effectively leaves a large chunk of the country in Russian hands.

The other, Trump-free scenario is less pressing, but a 2022 study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies revealed that only half of the conventional wars between states (i.e. not nuclear and not guerilla) end within a year. Moreover, “when interstate wars last longer than a year, on average they extend to over a decade.”

The Russian-Ukrainian war is already two-and-a-half years old (or ten years old if you count the first Russian invasion in 2014). How much longer do both sides have to wait, stuck in deadlock, before they agree on a ceasefire that stops the carnage and rescues their economies?

A ceasefire almost always makes sense in terms of human welfare, but it’s very hard to get there in practice. Both sides will be keenly aware that most ceasefires only stop the fighting. They do not undo the crimes, solve the issues, or recompense the victims.

They just freeze everything at the precise moment when the ceasefire is signed. That includes the border, and probably for decades: the Korean war and the Iran-Iraq war are prime examples. Every detail of a ceasefire has lasting consequences, so you need to think about it a long time before you sit down at the table together.

The Russians and the Ukrainians appear to be doing some thinking, but don’t expect anything to happen on this front before November. If Trump loses, the Russians would probably be willing to sign a deal that gives them around a quarter of the country, but Ukraine would want more territory back before negotiating a ceasefire, so again not yet.

And maybe not ever. Both parties will be conscious of the fact that the outcome of many, perhaps most long-lasting wars was decided by some event or development that was unforeseen by both participants when the war started. The temptation to hang on a little longer and hope something turns up is always strong.

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.