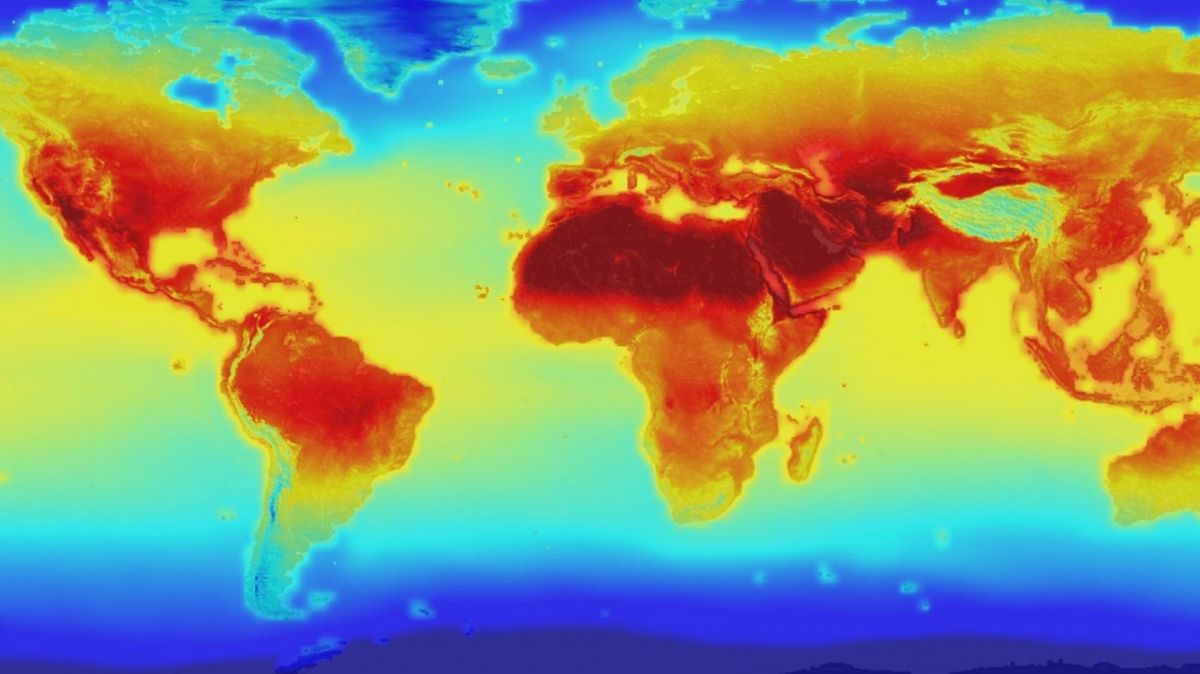

There are similar though less dramatic ocean heat waves popping up in unusual places like the North Pacific, the West African coast, and the equatorial part of the Indian Ocean. They are quite persistent, and some of the scientists who work on ocean heat are very worried.

“I don't want to say this is climate change, or natural variability or a mixture of both, we don't know yet. But we do see this change,” said Karina Von Schuckmann of Mercator Ocean International, lead author of the latest report on sea surface temperature. Many other climate scientists share her anxiety, but also her reluctance to commit to a conclusion.

Partly that reluctance is just the usual scientific caution when confronted with a new phenomenon, but it’s also because they really don’t want to believe that things have got this bad this fast. If the way the ocean is dealing with the heat it has absorbed is changing, it will certainly be changing for the worse, and that’s the last thing we need right now.

The world ocean, covering over two-thirds of the planet to an average depth of three and a half-kilometres, has been helpful in limiting the damage since the human race started emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases. In fact, it has absorbed a quarter of our carbon dioxide emissions, and 90% of the excess heat that has been trapped in the climate system.

However, the carbon dioxide is already making the oceans more acidic, which harms sea life, and we can safely assume that there is also a limit to how much CO2 the oceans can absorb (though we don’t know where it is). At some point, certainly, the oceans will not be able to absorb any more CO2, and the warming of the atmosphere will speed up a lot.

Similarly, at some point, the huge amount of excess heat that the oceans have absorbed will drive the sea surface temperature up dramatically and warm the atmosphere further, but we don’t know when.

Could that point be now? Yes, it could, but we don’t understand the ocean’s behaviour well enough to be sure yet. The main reason for the doubt about what’s really happening is the fact that we were expecting the recurrent climate phenomenon called El Niño to return around now anyway.

El Niño is part of a cycle of heating and cooling in the tropical part of the eastern Pacific (off Peru and Ecuador) that is strong enough to affect the whole global climate system. On average the cycle repeats around every seven years: the last El Niño was in 2015, and we’re due for another right about now.

New global records for high temperature are usually set during El Niño, while significant cooling happens during the intervals when the opposite condition, La Niña, dominates the system. So global warming has been held down for years by a prolonged La Niña, and it is now due to be accelerated for the next several years by a strong El Niño.

The problem for the scientists is that this cyclical leap in temperatures will be superimposed on the steady annual warming that human greenhouse gas emissions are causing – seven years of it since the last El Niño. We’re in for some unprecedently hot and stormy weather even if nothing new is happening.

But something new may be happening: major surface warming is also appearing in parts of the ocean that are not normally affected by the El Niño phenomenon. We and the scientists are both getting into unknown territory, and we’ll just have to wait and see what happens next.

The climate scientists (but not the rest of us) are acutely aware of how much they don’t know. Understanding of the climate system is expanding fast, but it is so complex that the field is still littered with ‘known unknowns’ – and probably lots of ‘unknown unknowns’ too.

Just for example, there is no clear consensus on what ‘climate sensitivity’ is. That is the fundamental question of how much CO2 and other warming gases in the air will cause a given amount of warming.

The universally agreed target is ‘never more than 2.0°C higher average global temperature’, and for practical purposes, we have agreed that this would be caused by 450 parts per million of ‘carbon dioxide equivalent’ in the atmosphere. But the real climate sensitivity, in the long run, could be as high as 4.5°C.

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.