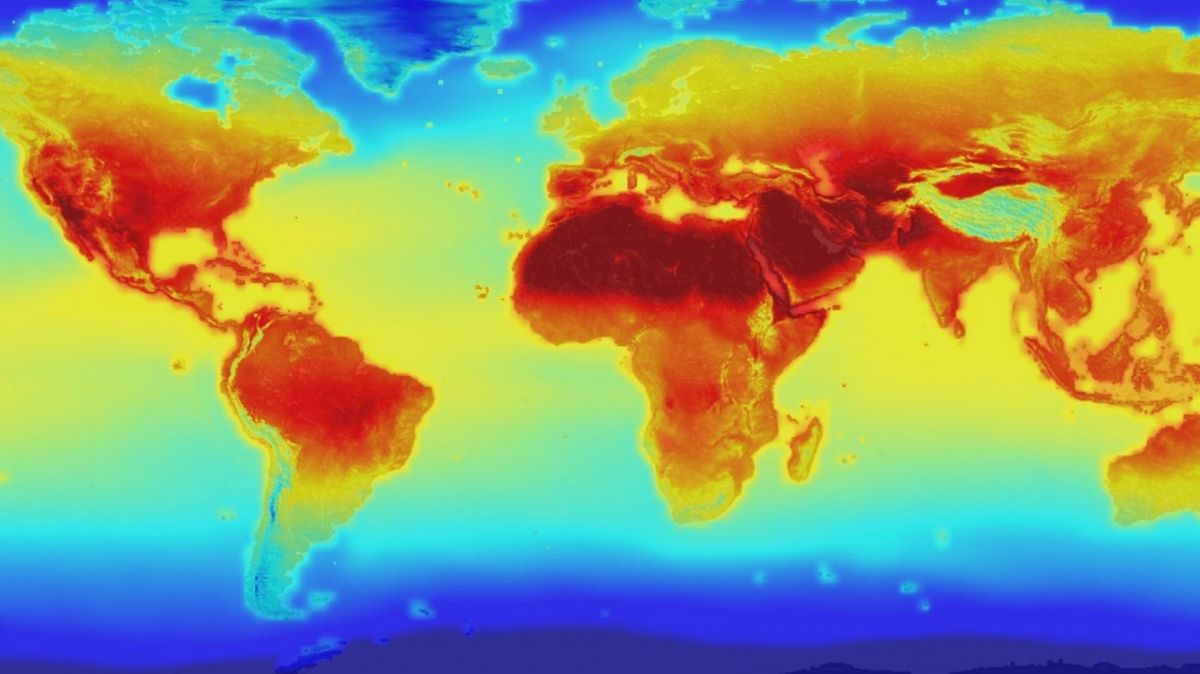

First they will acknowledge that 2024 has been the hottest year since we began keeping records a few centuries ago. This will be accompanied by the usual clucking about how naughty we have all been, not cutting our greenhouse gas emissions fast enough.

The only remedy for this, they will explain, is make those cuts now, and very fast. Almost none will mention that we have never managed to cut our net global emissions at all, except once in the peak Covid year when everybody was locked down.

Only if you can “believe six impossible things before breakfast,” like the White Queen in ‘Alice Through the Looking Glass’, could you believe that we can voluntarily shift from growing our global emissions by about 1% a year to slashing them by 7% a year in the next five years, which is the minimum change needed to avoid a catastrophe.

Human beings in large numbers simply cannot react that fast even when the catastrophes begin. The Philippines were hit by six cyclones (hurricanes) in one month last autumn – utterly unprecedented – and still there’s no big public demand there for a rapid switch from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

The second thing you will hear (if your media sources are reality-based) is that there was a big, unexplained leap in the warming in June 2023. The average global temperature jumped by three-tenths of a degree in one month. That is the amount had been predicted to occur over the next ten years.

This explains why we have seen a sudden upward lurch in wild weather all around the planet: bigger windstorms, fiercer forest fires, hotter, longer heat-waves, torrential rain causing floods and landslides, the lot.

And here’s the thing. Because climate scientists did not know what was causing the acceleration, most of them kept quiet until they had something more to say than “I don’t know.” The unfortunate side-effect of that was that the general public does not share their sense of panic – and no panic means no dramatic responses either.

Only in the past two months has a likely explanation emerged for the surge in temperature. Scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) think the world’s reflective cloud cover has shrunk in the past two decades by a small but significant amount. Therefore more sunlight is reaching the surface, which boosts global warming.

Unfortunately, the climate scientists still don’t know if this is just a one-time jump, after which the old rate of warming will resume. It could just as easily be a new, higher rate of warming that persists or even accelerates further. The ‘permanent emergency’ has actually arrived – but still the reluctance to level with the public continues.

In almost every report, there is a reassuring note to say that we haven’t really crossed any irreversible threshold yet. Yes, the average global temperature in 2024 has been higher than the ‘aspirational’ never-exceed warming of +1.5 degrees C, but don’t despair: it will be many years before we must accept that we have broken through that boundary for good.

This is pure sophistry. Temperatures fluctuate, so meteorologists usually calculate the average temperature of a place by averaging the variations over twenty years. However, when the change is always upwards, as it has been for the past fifty years, then taking into account temperatures from cooler years now long past gives you an answer that is much too low.

In present circumstances, the relevant average global temperature is simply whatever it is right now, and people who offer you less alarming interpretations are either deluded or seeking to deceive you. “If the trend holds up, we’re in trouble,” said Bjorn Stevens of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology. “We hope, hope it changes its direction tomorrow.”

If it doesn’t – if we are already “in uncharted territory”, as Gavin Schmidt, the director of GISS, puts it – what do we do next? There is no realistic short-term way to double or triple our emissions cuts: even if the will were there, the alternative energy sources take much time to build.

What we could do more quickly is to deploy various climate engineering methods that would reflect more sunlight and directly cool the planet. We could start putting sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere in a couple of years. With a crash programme, thickening low-level marine clouds could be active on a large scale within five years.

In practice, of course, we’ll probably spend that time arguing about it instead, while the heat-driven feedbacks cascade. Happy New Year.

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.