It’s the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), renowned for its ability to do big things on a relatively small budget (ca. $1 billion per year) that has made the running on the current project, a soft landing at the South Pole of the Moon.

It was India’s lunar orbiter Chandrayaan-1 that first reported the presence of water molecules in the lunar soil in 2008. The deep shadows of the southern polar region, never exposed to full sunlight, seems the best place to look for actual water ice, so ISRO followed up in 2019 with Chandrayaan-2, which made the first lunar landing attempt at the South Pole.

That ‘mother ship’ is still in orbit making observations, but the lander and surface rover it send down unfortunately crashed when the braking jets shut down a few seconds too early. Chandrayaan-3 is the follow-up, scheduled to send down its lander on the 23rd or 24th of this month.

Now here’s the thing. ISRO chose those dates because they mark the start of the two-week lunar day, to give their lander and the surface rover it carries the maximum amount of time to charge up their batteries in sunlight before the two-week lunar night arrives.

Rocosmos, the Russian space agency, initially chose the same landing date, obviously for the same reason. But when the Russian South Pole mission actually lifted off last week, Russia's space chief Yuri Borisov told state television that it would land on the 21st. “We hope to be first,”, he told workers at the Vostochny cosmodrome in the Russian Far East.

It’s physically possible, because the Russian rocket, Luna-25 (named in succession to the last Russian lunar mission in 1976, Luna-24) is a much bigger launcher carrying a lander only half the mass of the Indian one. If the Russians don’t spend time examining the landing site for possible hazards (as the Indians are doing), they could get their lander down first.

But the Indians could end up winning anyway, even though they’re not in the race. Landing at the South Pole before ‘Sunrise’ means that it will be harder for the Russian lander’s optics to distinguish between big rocks and deep hollows in a uniformly grey lunar landscape, and it could make a fatal mistake.

Roscosmos is willing to accept that risk (or has been ordered to accept it) because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent failures of its military to perform as advertised mean that the regime urgently needs to demonstrate technical competence to foreign customers. It also needs to boost domestic morale.

If both landers get down safely, however, there is no significant long-term advantage for the Russians in landing first (which is why the Indians are being very grown-up about the Russian gambit.) The Outer Space Treaty, signed in 1967, establishes the rule that no nation can own the Moon.

A subsequent Moon Agreement, signed in 1979, states more specifically that no nation, organisation or private individual can own resources on the Moon – but only four countries have signed it, not including the US, China or Russia.

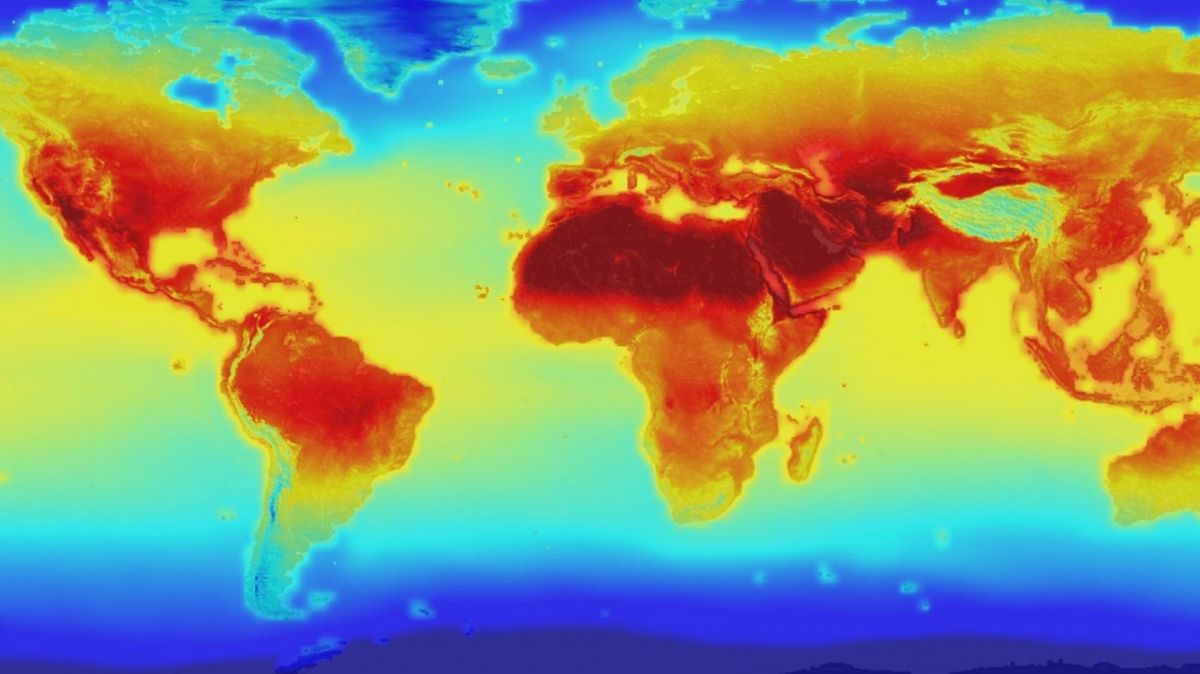

This is the first time some specific part of the Moon has become important for space-faring powers. If the South Polar region does have a lot of frozen water, then it is the obvious base for missions going to planetary destinations beyond the Earth-Moon system.

Just get yourself a reliable source of electrical power (solar panels or small nuclear reactors), and you can start melting the ice. There’s your drinking water sorted. Then split the water by electrolysis, and it will give you oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for rocket fuel. Add some hydroponics for food, and you’re basically independent for basic necessities.

It depends on just where the water ice is, but there could be serious competition for the best sites around the South Pole. The rivals would be China and Russia on one side – they plan to start building their Moon base, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), as early as 2026 – and the members of the US-led Artemis Accords on the other.

Artemis includes all the other countries capable of sending anything significant to the Moon (the US, India, France, Japan, Korea, Israel and the United Arab Emirates). The United States is planning to send a manned mission to the lunar South Pole in 2025, and the game between the ILRS and the Artemis Accords group will develop from there.

If there turn out to be many, widely distributed sources of water ice near the Pole, it will remain (as both sides insist it is) a friendly competition. If not, then not.